If you’ve never created a Web application before because you

didn’t have time to climb the learning curve, ASP.NET could be your big chance.

This chapter shows you how to utilize everything you learned in the previous

chapter about building Windows Forms applications (plus a few extra twists) in

building ASP.NET Web Form Applications. It also demonstrates how to reuse the

business objects created in the previous chapter by taking you step-by-step

through the process of creating an ASP.NET Web Application.

Microsoft made a mistake a number of years ago

underestimating the tremendous impact the Internet would have on our world.

After realizing the error of its ways, Microsoft responded by creating Active

Server Pages (ASP)—a platform for creating, deploying, and running Web

applications. Although ASP contained some interesting technologies, it

definitely fell in the category of a “knee jerk” reaction. ASP allowed you to

get the job done, but not in the most efficient way.

In contrast, Active Server Pages.NET (ASP.NET) is a vast

improvement over ASP. Rather than using scripting languages to write

server-side code that is interpreted at run time, ASP.NET allows you to use

fully object-oriented languages such as C# and Visual Basic .NET to create code

that can be compiled and cached on the server for faster performance. ASP.NET

also provides a more robust event-driven model allowing events to be raised on

the client and handled on the server. In addition, Microsoft has done a great

job making the Windows Forms and Web Application architecture and design tools

similar enough so a developer can move from one to the other without incurring

a huge learning curve.

ASP.NET actually encompasses two different technologies—Web

Forms and Web Services. This chapter focuses on Web Forms. To learn about Web

Services, see Chapter 12, “XML Web Services”.

For information on using ASP.NET with Visual FoxPro 7, check out

the white paper by Cathi Gero (this book’s technical editor!) at http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/default.asp?url=/library/en-us/dnfoxgen7/html/usingaspnetwithvfp7.asp

A typical Web application is comprised of Web pages,

configuration files, code files containing business object classes, images, and

references to external .NET assemblies. In this walk-through, you will see how

each element is used in an ASP.NET Web application.

A Web application starts the first time a user requests a

page from the server (for example, by entering the URL of the Web site). The

application continues to run until the Web server (the physical machine) is

restarted, IIS is restarted, or if any of the application’s configuration files

are edited.

There are a number of configuration settings where you specify

different conditions for starting a new process in your Web

application—percentage of memory used, number of unprocessed requests waiting in

the request queue, and so on. Adjusting these settings can help make your Web

applications more available and more stable. For more information, see the

“Machine.config” and “Web.config” sections later in this chapter.

By default, the Web is a stateless environment. If you

send multiple requests from your Web browser to a particular Web site, you

automatically disconnect and reconnect between each request. A series of

successive requests coming from a single browser is known as a session.

The first request sent from a client browser to a Web application begins a

session for that client. By default (you can change this setting), if the

client is idle for longer than 20 minutes, the session is automatically ended

by the server.

Based on this disconnected model, your Web applications need

some way to keep track of all the user sessions. ASP.NET steps in the gap and

keeps track of each user session automatically. It does this by generating a

unique Session ID when a client sends its first request to your Web site. This

Session ID is passed back to the client by means of a cookie or modified URL.

For more information on sessions, check out the “The Session Object” section

later in this chapter.

As in Chapter 9, “Building .NET Windows Forms

Applications”, you will learn about creating ASP.NET Web applications by

example. In this chapter you will recreate the Windows Forms application from

chapter 9 as a Web Forms application.

To create a new Web Application:

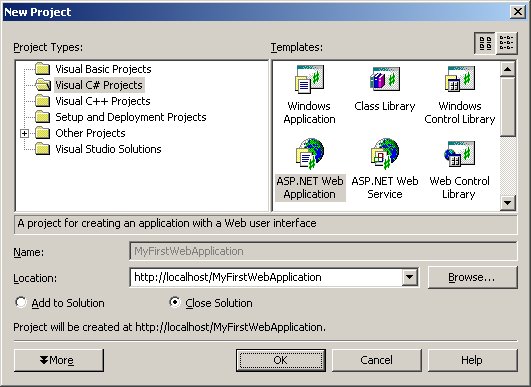

1. From

the Visual Studio .NET Start Page,

click the New Project

button.

2. In

the New Project

dialog’s Project Types pane,

select Visual C# to

create a C# Web application or Visual

Basic .NET to create a VB .NET Web application. In the Templates pane on the

right, select ASP.NET Web

Application.

3. Notice

that the Name text box is

disabled and contains the text “WebApplication1” and (if you’re creating the

Web Application on your local machine) the Location

text box contains the text “http://localhost/WebApplication1”. To change the

name of the Web application, you must change the name of the directory in the Location text box. This

is different from a Windows Forms application where you can change the name of

the application and the directory independently. In this example, change the

last part of the directory name from “WebApplication1” to

“MyFirstWebApplication”. As you type this in, notice that it automatically

changes the Name of the

application to “MyFirstWebApplication” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Location text box specifies the

virtual root directory for your Web application.

4. Click

the OK button.

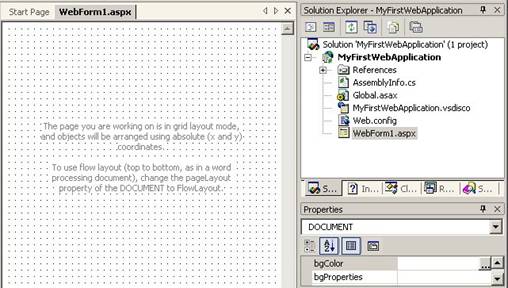

At this point, you may feel a

bit like Al Gore when the “Creating the Web” dialog displays. While this dialog

is displaying, VS .NET creates a new application for you using the ASP.NET Web

Application template you selected. After a few moments, a new form named

WebForm1.aspx is displayed in design mode in the Visual Studio .NET IDE (Figure

2).

Figure 2. Visual Studio .NET creates an ASP.NET

Web Application from the template you select in the New Project dialog.

As you can see this is already very similar to creating a

Windows Forms application—VS .NET created an application for you containing a

single form. Before taking a closer look at this Web form, first you’ll do a

little housekeeping and then learn a little more about what happens behind the

scenes when using VS .NET to create a Web Forms application.

The housekeeping involves renaming the project’s

namespace. When you create a new Web application, VS .NET automatically sets

your project’s namespace to the same name as the project—which is most likely

not what you want!

If you’re using Visual Basic .NET, before you can change the

project’s namespace, you must first close the WebForm1.aspx. To do this, you

can simply click the close button [X]

to the right of the VS .NET IDE tabs.

To change the project’s namespace, in the Solution Explorer,

right-click on the project (the second node in the Solution Explorer)

and select Properties from

the shortcut menu, which launches the Property

Pages dialog. In the left pane under the Common Properties folder,

select General (if it’s

not already selected).

If you’re using C#, in the right pane, change the Default Namespace from

“MyFirstWebApplication” to “HW.NetBook.Samples”. If you’re using VB .NET, in

the right pane, change the Root

namespace to “HW.NetBook.Samples”. When you’re done, click the OK button to save

changes.

Now you just need to change any existing references to the

old name space. Select Edit | Find

and Replace | Replace in Files from the main menu to launch the Replace in Files dialog.

In the Find What box,

enter “MyFirstWebApplication” and in the Replace

with box enter “HW.NetBook.Samples” (make sure you type the case

correctly if working with C#). Now click the Replace

All button, which launches a Replace

All warning dialog. Just click OK

to ignore the warning. After clicking OK,

a dialog appears telling you how many occurrences were replaced. If you’re

using C#, it should say, “4 occurrence(s) replaced”. If you’re using Visual

Basic .NET it should say, “2 occurrence(s) replaced”.

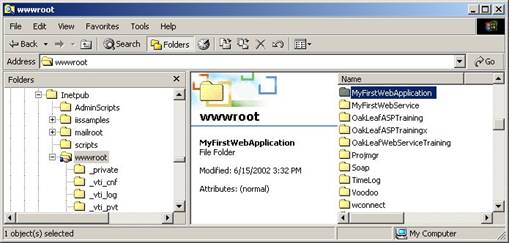

When you created the new Web application and specified

the location of the application as “http://localhost/MyFirstWebApplication”

(Figure 1), you were actually specifying a virtual

directory. In the world of IIS, a

virtual directory is a directory on the Web server that contains a Web

application. It is virtual in the sense that it does not describe the exact

physical location of a directory on the machine, but provides a higher-level

virtual name that, behind the scenes, is associated with a real

directory.

In the Location string, the “localhost” directory refers to

the home directory of the Web Server. In IIS, this is set up by default to be

c:\inetput\wwwroot, and therefore the MyFirstWebApplication virtual directory

would be physically located in the c:\inetpub\wwwroot directory (Figure 3).

Figure 3. When you create a new Web application,

VS .NET creates a virtual directory that, by default, is physically located in

the c:\inetpub\wwwroot directory.

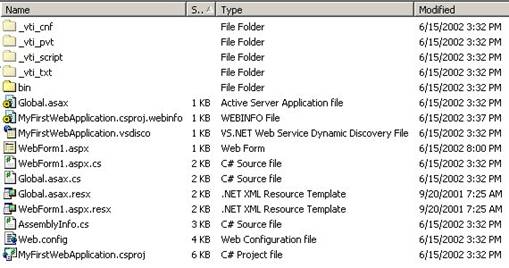

If you look in the new MyFirstWebApplication directory from

within Windows Explorer, you’ll see that VS .NET has created a variety of files

and subfolders in your new virtual directory (Figure 4).

Figure 4. VS .NET places a variety of files in

your Web application’s virtual directory.

You’ll be taking a closer look at some of these files in the

next section, but for now, notice there is a project file in this directory

(.csproj for C# or .vbproj forVB .NET ),

but no solution file (.sln). VS .NET puts the solution file in a subfolder of

the “My Documents\Visual Studio Projects\” directory. In the example, it

creates a subfolder named “MyFirstWebApplication” and places the MyFirstWebApplication.sln

and associated .suo file in this folder. So, when you need to reopen your Web

application after restarting Visual Studio .NET, you can find your solution in

this folder.

However, this does not mean your Web application’s source

code is stored in two different places. Remember the solution is simply a

container—similar to Visual FoxPro’s project (PJX) file—with links to projects

and files. For now, all your source code is stored in your Web application’s

virtual directory.

Now look a little closer at “WebForm1” in your new Web

application. A Web form can be viewed in either Design mode (Figure 2) or in

HTML mode. If WebForm1 is not currently opened in the IDE, double-click on the

form in the Solution Explorer. To switch to HTML mode, either click on the HTML

tab at the bottom left of the Web Forms designer or right-click the Web form

and select View HTML Source

from the shortcut menu. As you make changes to the Web form in design mode, VS

.NET automatically changes the HTML source accordingly. On the other hand, if

you know something about HTML, you can manually edit the HTML source and your

changes will be reflected in Design mode.

If you view the HTML source of WebForm1, you will see the

following HTML.

In C#:

<%@ Page

language="c#" Codebehind="WebForm1.aspx.cs"

AutoEventWireup="false" Inherits="HW.NetBook.Samples.WebForm1

%>

<!DOCTYPE HTML

PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN" >

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<title>WebForm1</title>

<meta name="GENERATOR" Content="Microsoft

Visual Studio 7.0">

<meta name="vs_defaultClientScript"

content="JavaScript">

<meta name="vs_targetSchema"

content="http://schemas.microsoft.com/intellisense/ie5">

</HEAD>

<body MS_POSITIONING="GridLayout">

<form id="Form1" method="post" runat="server"

>

</form>

</body>

</HTML>

If you’re using Visual Basic .NET, the only line that’s

different is the first line at the top of the page:

<%@ Page language="vb"

Codebehind="WebForm1.aspx.vb" AutoEventWireup="false"

Inherits="HW.NetBook.Samples.WebForm1 %>

This first line of code is known as a page directive.

The “Page Language” attribute tells the compiler the language used for the code

contained in the Web page (typically “c#” or “vb”). The “CodeBehind” setting

specifies a code-behind file associated with the .aspx file—in this case

either WebForm1.aspx.cs (C#) or WebForm1.aspx.vb (VB .NET).

An ASP.NET Web page consists of two main parts—the

visible representation stored in the .aspx file and associated code stored in a

.cs or .vb code-behind file (which gets its name from “the code file behind the

form”.) This structure lets you separate the user interface from the executable

code. When you create a Web page in Visual Studio .NET, it automatically creates

both an .aspx file and a code-behind file. It associates the two by placing the

name of the code-behind file in the .aspx page directive as seen in the

previous section.

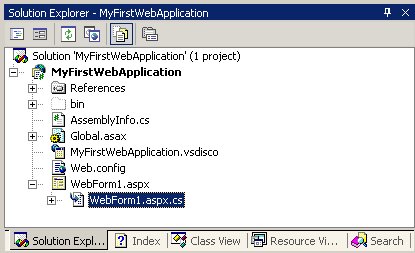

If you look at the list of files in the Solution Explorer, by

default, you won’t see the code-behind file. To make this file visible, click

on Solution Explorer’s “Show All Files” icon button, the second button from the

right at the top of the window. When you click this button, a plus sign appears

next to the WebForm1.aspx file. If you expand the plus sign, you will see the

associated code-behind file (Figure 5).

Figure 5. If you click on the “Show All Files”

icon button in the Solution Explorer, you can see your Web form’s code-behind

file.

To view the contents of the code-behind file, double-click

the file in the Solution Explorer and VS .NET opens it in the IDE. The

code-behind file contains the following code-behind class definition.

In C# (excluding the namespace directives):

public class WebForm1 : System.Web.UI.Page

{

private void

Page_Load(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

// Put user code to

initialize the page here

}

}

In Visual Basic .NET:

Public Class

WebForm1

Inherits System.Web.UI.Page

[Web Form Designer

Generated Code]

Private

Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As System.Object,ByVal e As _

System.EventArgs) Handles MyBase.Load

'Put user code to initialize the page

here

End

Sub

End Class

As you can see, VS .NET automatically added code to this

code-behind file that defines a class named WebForm1 derived from the

System.Web.UI.Page class.

Now here’s the interesting part—look back at the

WebForm1.aspx page directive:

<%@ Page language="c#"

Codebehind="WebForm1.aspx.cs" AutoEventWireup="false"

Inherits="HW.NetBook.Samples.WebForm1 %>

Notice the “Inherits” attribute specifies the .aspx page

inherits from the WebForm1 class (belonging to the HW.NetBook.Samples

namespace). When you compile your Web application under Visual Studio .NET, the

.aspx file is compiled into a class derived from the code-behind class! This

means you can add methods and other members to the WebForm1 code-behind class

and they will be inherited by the class created from the .aspx file at runtime.

You will see examples of how this works later in this chapter.

Before diving further into the details of ASP.NET Web

applications, you can get some immediate gratification by creating a simple

“Hello .NET World!” Web page.

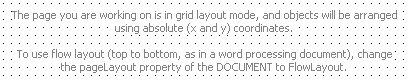

To start, select the WebForm1.aspx file in design mode. This

involves clicking the WebForm1.aspx tab and making sure the Design tab at the bottom

left of the IDE is selected. Notice the text in the middle of the Web form (Figure

6) states the Web form is set to work in “grid layout” mode, and objects

dropped on the form are arranged using absolute coordinates. For this example,

you will change the Web form to use “flow layout”, which is more like a word

processing document (you’ll use grid layout mode later in this chapter). To

switch to flow layout, go to the Properties Window and change the pageLayout property to

“FlowLayout”. When you do this, the dotted grid lines disappear and the text in

the middle of the Web form changes accordingly.

Figure 6. By default, Web forms are set to work

in “grid layout” mode, but you can change their mode to “flow layout” to behave

more like a word processing document.

Now, drag and drop a label from the VS .NET Toolbox onto the Web form

(make sure the Web Forms

tab of the Toolbox is

selected). The label is automatically placed in the upper left-hand corner of

the form. Next, go to the Properties Window, change the (ID) property from

“Label1” to “lblHelloWorld”, and then change the Text

property to “Hello .NET World!”. This changes the visible text of the label on

the Web form accordingly.

Now change the font of the label. Click to the right of the

label control on the Web form (click at the point where your mouse pointer is

an “I-beam” rather than a quad-arrow) and you should see the Formatting toolbar

(Figure 7).

Figure 7. The Formatting toolbar allows you to

change the appearance of visual elements on your Web form.

Open the combo box that is set to “Normal” by default and select “Heading 1”

instead as shown in Figure 7. When you do this, it increases the font size and

bolds the label text.

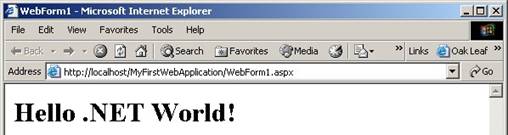

Now you’re ready to compile and run your Web application. To

do this, click the Start

button or press F5.

When the Web application runs, you should see the text “Hello .NET World!” in

large, bold letters (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The obligatory Hello World application

provides immediate gratification for building your first Web application.

Now that you’ve gotten your first, simple Web application

under your belt, it’s time

for a quick overview of the different types of controls available to you when creating Web Forms applications.

for a quick overview of the different types of controls available to you when creating Web Forms applications.

Different types of controls

There are three basic types of Web controls in ASP.NET:

·

HTML controls

·

HTML server controls

·

Web Forms controls

HTML controls are the “classic” controls such as

<h1>, <input>, and <div>. These

controls are not processed by the Web server, but are sent directly to the client browser for rendering. If you want the lightest-weight (but least capable) controls for your Web forms, use HTML controls.

controls are not processed by the Web server, but are sent directly to the client browser for rendering. If you want the lightest-weight (but least capable) controls for your Web forms, use HTML controls.

HTML server controls are one step above regular HTML

controls regarding capability. Although the HTML for these controls looks very

similar to classic HTML controls, they have the added ability to enable

server-side processing, which includes data binding and responding to events

(discussed later in this chapter). These controls are designed to be most like

original HTML controls, so developers who are familiar with classic HTML

controls should feel very comfortable using these new ASP.NET counterparts.

Web Forms controls are the most capable of all the

ASP.NET controls. Rather than trying to imitate classic HTML controls, Web

Forms controls more closely resemble Windows forms controls. They can also

enable server-side processing, as do HTML server controls, but they are even

more powerful. For example, they can automatically detect the level of HTML

support provided by a browser and adjust their HTML output accordingly. In

addition,

they are useful in creating more complex controls such as the ad rotator and calendar

controls. Based on their advanced capabilities, these are the controls used for the examples

in this chapter.

they are useful in creating more complex controls such as the ad rotator and calendar

controls. Based on their advanced capabilities, these are the controls used for the examples

in this chapter.

To use Web Forms controls on your Web pages, make sure you have

the Web Forms tab selected in Visual Studio .NET’s Toolbox when you drag and

drop controls on your forms.

Now that you know about the different types of controls you

can use in creating Web Forms, take a closer look at what’s going on behind the

scenes with ASP.NET.

Take a look at another file shown in the Solution

Explorer—the global.asax file. When you first create a new Web Application or

Web Service through Visual Studio .NET, a global.asax file is automatically

placed in the root directory of your application. At run time, the global.asax

file is automatically parsed and compiled by the CLR into a

dynamically-generated class derived from the .NET HttpApplication base class.

As its name suggests, this class represents a Web application and it’s used to

process requests from users.

If you right-click the global.asax file and select Open With from the

shortcut menu, it displays the Open

With dialog. Select “Source Code (Text) Editor” and then click

the Open button. When

the file opens, you will see an application directive similar to the

page directive found in the WebForm1.aspx file.

Here it is in C#:

<%@ Application

Codebehind="Global.asax.cs"

Inherits="HW.NetBook.Samples.Global"%>

And in Visual Basic .NET:

<%@ Application Codebehind="Global.asax.vb"

Inherits="HW.NetBook.Samples.Global"

%>

The “Codebehind” attribute specifies the name of the

associated code-behind file, and the “Inherits” attribute specifies the class

from which the global.asax file inherits—in this case

HW.NetBook.Samples.Global.

Right-click on global.asax in the Solution Explorer and

select View Code from the

shortcut menu to open the code-behind file named global.asax.cs (C#) or

global.asax.vb (VB .NET). If you look at the code contained in this code-behind

file, you’ll see it defines a class named Global derived from the

System.Web.HttpApplication class.

In C#:

public class Global : System.Web.HttpApplication

{

public Global()

{

InitializeComponent();

}

// The rest of the class

not shown for space reasons

}

In Visual Basic .NET:

Public Class Global

Inherits

System.Web.HttpApplication

#Region " Component Designer Generated Code "

Public Sub New()

MyBase.New()

'This call is

required by the Component Designer.

InitializeComponent()

'Add any

initialization after the InitializeComponent() call

End Sub

' The rest of the class

not shown for space reasons

#End Region

End Class

The first time a user requests any resource or URL

within your Web application, your Web application starts and the global.asax

file is parsed and compiled into a class derived from this Global class. The

object instantiated from this class processes requests from the user.

If you look further down in the class definition, you’ll see

application and session event handlers for the following events:

·

Application_Start

·

Session_Start

·

Application_BeginRequest

·

Application_EndRequest

·

Application_AuthenticateRequest

·

Application_Error

·

Session_End

·

Application_End

You place code in any of these empty event handler methods to

respond to the corresponding ASP.NET events. You can also add your own custom

members (such as methods, properties, fields) to this class. For example, at

Application Startup you may want to call Server.MapPath to determine the

current server path and store it in a static variable. This saves you from

making this call over and over again (and incurring a performance hit)

throughout your application. Add the following code shown in grey to your

global.asax file.

In C#:

public class

Global : System.Web.HttpApplication

public Global()

{

InitializeComponent();

}

protected void Application_Start(Object sender, EventArgs e)

}

// The rest of the class definition not shown here for space

reasons

}

In Visual Basic .NET:

Public Class Global

Inherits

System.Web.HttpApplication

#Region " Component Designer Generated Code "

Public Sub New()

MyBase.New()

'This call is

required by the Component Designer.

InitializeComponent()

'Add any

initialization after the InitializeComponent() call

End Sub

’ The rest of the class

not shown for space reasons

#End Region

Protected Sub

Application_Start(sender As [Object], e As EventArgs)

End Sub

'Application_Start

End Class

Now you can reference the static ServerPath property from

anywhere within your Web application. For example, the following code derives a

fully qualified path to a config.xml file by prepending the value stored in

Global.ServerPath to the file name.

Here’s the code in C#:

string ConfigFile = Global.ServerPath +

"\\config.xml";

And here it is in Visual Basic .NET:

Dim ConfigFile As String = Global.ServerPath +

"\config.xml"

As a subclass of the HttpApplication base class, this

Global class exposes some important objects globally accessible throughout your

Web application. Some of these are:

·

Server

·

Application

·

Session

·

Response

·

Request

·

User

·

Site

Each of these objects is detailed in the following sections.

The Server object

The Server object is an instance of the

System.Web.HttpServerUtility class. This object has properties and methods

allowing you to get and set information regarding the machine where the Web

server is running as well as helper methods for processing Web requests.

Here is an example of accessing the MachineName property of

the Server object.

In C#:

string ServerName = Server.MachineName;

In Visual Basic .NET:

Dim ServerName As String = Server.MachineName

Notice you simply need to type the name of the Server object

followed by the property or method to access it from code. Table 1 lists

some other commonly used members of the Server object.

Table 1. Commonly used members of the Server

object

Member name

|

Type

|

Description

|

MachineName

|

Property

|

Property that stores the server’s

computer name

|

ScriptTimeout

|

Method

|

Gets and sets the server’s request

time-out

|

ClearError

|

Method

|

Clears the last error

|

GetLastError

|

Method

|

Returns the last error

|

HtmlDecode

|

Method

|

Decodes a string that has been

encoded to eliminate invalid HTML characters

|

HtmlEncode

|

Method

|

Encodes a string to be displayed in

a browser

|

MapPath

|

Method

|

Returns the physical file path of

the specified virtual directory

|

Transfer

|

Method

|

Transfers execution to the

specified Web page

|

UrlDecode

|

Method

|

Decodes a string encoded for HTTP

transmission and sent to the server in a URL

|

UrlEncode

|

Method

|

Encodes a string for HTTP

transmission from the server to the client via the URL

|

The Application object

The Application object is an instance of the

System.Web.HttpApplicationState class allowing you to share global data and

objects across multiple sessions in an ASP.NET application. The Application

object has a Contents dictionary collection property where you can add data and

objects at runtime that can be accessed from any user session. Although you can

specifically reference the Contents collection property to add or access items

in the collection, because it has been defined as an indexer, you simply access

the Contents collection by using the indexer syntax (For more information on

Indexers, see Chapter 5, “Object Orientation in C# and Visual Basic.

NET”).

For example, add the following code shown in grey to the

Application_Start method of the global.asax file. This code adds a new string

object named “ConnectString” to the Contents collection.

In C#:

protected void Application_Start(Object sender,

EventArgs e)

{

}

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Sub Application_Start(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As

EventArgs)

End Sub

To access this string, you use a similar syntax, but you must

cast the value to the appropriate type—this is because all objects stored in

the collection are stored as the Object type. For example, the following code

gets the value of the ConnectString item from the Application object.

In C#:

string Connect = (string)Application["ConnectString"];

In Visual Basic .NET:

Dim Connect As String =

CStr(Application("ConnectString"))

In a nutshell, the Application object provides an easy way to

store data and objects accessible from any user session.

Application object pitfalls

There are a few things to watch out for when using the

Application object. First of all, if you have a Web farm (a single Web site

that contains multiple Web servers) or a Web garden (a single Web server

machine with multiple processors), be aware that the Application object is

specific to a single process running on a single processor. This means sessions

running on different processors or different physical machines do not have

access to the same Application object. If you need truly global access to data

from all sessions running in a Web farm or Web garden, you can store the

information in a globally accessible database or data file, such as an XML

file.

If you allow clients to modify global data stored in the

Application object, you need to be aware of concurrency issues. Take for

example the following code making use of a Counter value in the Application

object.

In C#:

int Count = (int)Application["Counter"];

Count += 1;

Application["Counter"] = Count;

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Dim Count As Integer = CInt(Application("Counter"))

Count += 1

Application("Counter") = Count

What happens if another session increments the Application

object’s Counter value between the time this session gets the value, increments

it, and stores it back to the Application object? The first session’s increment

of the Counter would be lost. To prevent this, you call the Application

object’s Lock and Unlock methods.

In C#:

Application.Lock();

int Count = (int)Application["Counter"];

Count += 1;

Application["Counter"] = Count;

Application.UnLock();

In Visual Basic .NET:

Application.Lock()

Dim Count As Integer = CInt(Application("Counter"))

Count += 1

Application("Counter") = Count

Application.UnLock()

The call to the Application object’s Lock method causes the

Application object to lock access to any items subsequently accessed in the

Contents collection. For example, once the second line of code executes, the

“Counter” variable is locked to any other sessions, until the call to

Application.Unlock is made. Obviously, if you lock the Application object, you

want to unlock it as quickly as possible! Also beware of any “deadly embrace”

problems you may encounter when you allow a piece of code to lock more than one

variable. If Process A has the first variable locked and Process B has the

second variable locked, they could each be waiting indefinitely for the other

process to unlock the variable.

Fortunately, if you don’t unlock the Application logic after

locking it, the Web server unlocks the Application object when it finishes

processing the .aspx file.

The Session object

The Session object is an instance of the

System.Web.SessionState.HttpSessionState class. In the same way the Application

object stores information accessible from all sessions in an application, the

Session object stores session state—information accessible from all Web forms

in a single user session. The unique session ID keeps each session’s data

separate from all other session data.

The Session object also has a Contents dictionary collection

property accessible with indexer syntax. For example, the following code adds a

new string object named “ISBN” that contains an ISBN number to the Contents

collection.

In C#:

Session["ISBN"] = "0-596-00171-1";

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Session("ISBN") = "0-596-00171-1"

Here’s an example of accessing this item in C#:

string ISBN = Session["ISBN"];

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Dim ISBN As String = Session("ISBN")

The Session object is extremely useful for storing

information that needs to be passed from one page to the next in a given

session.

By default, Session state is stored in memory outside of the

ASP.NET process. This means if the server is restarted or crashes (IIS—not the

physical server), session state is not lost! For other Session state options

see the “Caching data and objects” section later in this chapter.

The Session object has a number of other useful properties

and methods. Some of the most frequently used members are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Commonly used members of the Session

object

Member name

|

Type

|

Description

|

IsCookieless

|

Property

|

If True, specifies the session ID

is embedded in the URL. If False, indicates the session ID is stored in an

HTTP cookie.

|

IsNewSession

|

Property

|

Returns a boolean value indicating

if the session was created with the current request.

|

Mode

|

Property

|

Specifies how session state is

cached. The value of this setting is

one of the four SessionStateMode enumerations: InProc (the default), Off, SqlServer, StateServer. For more information on session state caching, see the “Caching Data and Objects” section later in this chapter. |

SessionID

|

Property

|

Gets the current unique session ID.

|

Abandon

|

Method

|

Cancels the current session.

|

Clear

|

Method

|

Clears all values from the session

state.

|

The Response object

The Response object is an instance of the System.Web.HttpResponse

class and is one of the most important objects in ASP.NET. This object sends

information from the Web server to

the client.

the client.

For example, the following code displays a simple “Hello .NET

World” message to the client’s browser.

In C#:

Response.Write("Hello .NET World");

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Response.Write("Hello .NET World")

The Response object can also redirect to another page. The

following example redirects the client to the Hentzenwerke web site.

In C#:

Response.Redirect("http://www.hentzenwerke.com");

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Response.Redirect("http://www.hentzenwerke.com")

Table 3 lists some other commonly used properties and

methods of the Response object.

Table 3. Commonly used members of the Response

object

Member name

|

Type

|

Description

|

Buffer

|

Property

|

Specifies whether output should be

buffered (wait until the entire Response is finished processing).

|

Expires

|

Property

|

Specifies the number of minutes

before a page cached in a browser expires.

|

IsClientConnected

|

Property

|

Returns a boolean value indicating

if the client is still connected.

|

Flush

|

Method

|

Sends all buffered output to the

client.

|

Redirect

|

Method

|

Redirects a client to the specified

URL.

|

Write

|

Method

|

Writes the specified information to

the client.

|

The Request object

The Request object is an instance of the

System.Web.HttpRequest class, and one of the most important ASP.NET objects.

This object allows you to read HTTP values sent from the client to the Web

server. You learn a lot about the client from the properties of the Request

object.

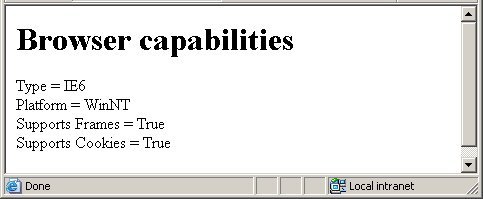

For example, the following code uses the Browser property of

the Request object to return an HttpBrowserCapabilities and display information

about the client’s browser (Figure 9).

In C#:

HttpBrowserCapabilities bc = Request.Browser;

Response.Write("<H1>Browser

capabilities</H1>");

Response.Write("Type = " + bc.Type +

"<br>");

Response.Write("Platform = " + bc.Platform +

"<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Frames = " + bc.Frames +

"<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Cookies = " +

bc.Cookies + "<br>");

In Visual Basic .NET:

Dim bc As HttpBrowserCapabilities = Request.Browser

Response.Write("<H1>Browser

capabilities</H1>")

Response.Write(("Type = " + bc.Type +

"<br>"))

Response.Write(("Platform = " + bc.Platform +

"<br>"))

Response.Write(("Supports Frames = " + bc.Frames +

"<br>"))

Response.Write(("Supports Cookies = " +

bc.Cookies + "<br>"))

Figure 9.You can use the Request object to find

out information about a client’s browser.

The User object

The User object is an instance of the System.Security.Principal.WindowsPrincipal

class. You can use this object to check the Windows group membership of the

current user, if the user has been authenticated. For example, the following

code uses the IsInRole method of the User object to see if the user is in the

Windows Group “Guests”.

In C#:

bool IsAdministrator = User.IsInRole("Guests");

In Visual Basic .NET:

Dim IsAdministrator As Boolean =

User.IsInRole("Guests")

For more information on users and security, see Chapter 14,

“.NET Security”.

The Site object

The Site object is an instance of the

System.Security.Policy.Site class. This object can be used to determine the Web

site where an assembly originates.

For more information on security, see Chapter 14, “.NET

Security”.

If you make changes to the global.asax file while the

Web application is running, ASP.NET page framework detects the change. It

completes all outstanding requests, sends the Application_OnEnd event to any

listeners, and restarts the application.

There are two main configuration files used by ASP.NET:

·

Machine.config

·

Web.config

In ASP.NET, configuration information is stored in XML

configuration files. This makes remote administration a snap because you can

edit these files using any standard XML parser or text editor. In addition,

these files can be edited without stopping and restarting the server. Once the

changes are made to the configuration files, the new settings apply to any new

client requests.

The Machine.config file is the root configuration file

that provides default settings for the entire Web server. This file is located

beneath your Web server’s Windows directory in the <Windows

Directory>\Microsoft.NET\Framework\<version>\CONFIG folder.

Each Web application inherits default configuration settings

from the Machine.config file.

Each Web application can have one or more Web.config

files that apply ASP.NET configuration settings to its own directory and all

subdirectories. These files are used to override or extend the configuration

settings inherited from the Machine.config file. For

more information on how this inheritance works, check out the .NET Help topic “Configuration Inheritance”.

more information on how this inheritance works, check out the .NET Help topic “Configuration Inheritance”.

Here are some examples of settings found in the Web.config

file:

<compilation

defaultLanguage="c#"

debug="true"

/>

The compilation element contains a defaultLanguage setting

indicating the default language of your Web application. The debug setting

specifies whether you want the compiler to create debug information for your

pages. This is obviously desirable when first creating and testing your Web

application. However, when you’re ready to deploy a completed, well-tested

application, you should set debug to “false” to generate a more compact (and

faster) version of your Web application devoid of debug information.

Here’s another element in Web.config named “customErrors”.

<customErrors

mode="RemoteOnly"

/>

The mode setting in this element specifies how to display

ASP.NET error messages to users. This setting has three possible values as you

can see by reading the comments above the setting in the Web.config file:

·

On – Always display custom (friendly) messages

·

Off – Always display detailed ASP.NET error

information

·

RemoteOnly – (the default) Display custom

(friendly) messages to users not running on the local Web server. This setting

is recommended for security purposes, so you do not display application detail

information to remote clients.

For more information on these and other settings, check out

the .NET Help topic “ASP.NET Configuration”.

Creating the Customer Orders Web form

Now you’re ready to create a Customers Orders Web form

similar to the Windows Form created in the previous chapter. Before creating

this form, remove the “Hello .NET World!” label added earlier in this chapter.

To do this, right-click on the label in design mode and select Delete from the shortcut

menu. Also, set the style back from “Heading1” to “Normal”

by clicking on the Web form in the location where the label was then select “Normal” from the Format

toolbar.

Next, rename the Web form file to something more

meaningful. In the Solution Explorer, right-click the WebForm1.aspx file and

select Rename from the

shortcut menu. Change the name of the file to CustomerOrders.aspx. Notice this

also changes the name of the code-behind file (CustomerOrders.aspx.cs in C# or

CustomerOrders.aspx.vb in VB .NET). Now that you’ve changed the name of the

source code file, you need to change the name of the actual Web form class. To

do this, double-click the code-behind file in the Solution Explorer, which

opens the code file in the Visual Studio .NET IDE. Change the name of the class

from “WebForm1” to “CustomerOrders”.

In C#:

public class CustomerOrders : System.Web.UI.Page

In Visual Basic .NET:

Public Class CustomerOrders

Inherits

System.Web.UI.Page

Now it’s time to add some controls to the Web form.

Make sure the CustomerOrders.aspx is open in design mode, then drag and drop a

label from the VS .NET Toolbox

onto the Web form. With the label control selected, go to the Properties Window

and change the (ID)

property to “lblCustomerID” and the Text

property to “Customer ID:”.

Next, drag and drop a TextBox control from the Toolbox to the Web form.

The text box should be automatically placed to the right of the label. Go to

the Properties Window and change the (ID)

property to txtCustomerID.

Now add a Submit button to the Web form. Click to the right

of the text box—this places the cursor to the immediate right of the text box.

Press the space bar three times to add a bit of space between the text box and

the button you’re getting ready to add. Next, drag and drop a Button from the Toolbox to the right of

the text box. With the button selected, go to the Properties Window and set the

button’s (ID) property to

“btnSubmit” and its Text

property

to “Submit”.

to “Submit”.

Before adding the next control, you need to create a new line

in the Web form. To do this, click to the immediate right of the text box and

press the Enter key. This should drop the cursor down beneath the Customer ID

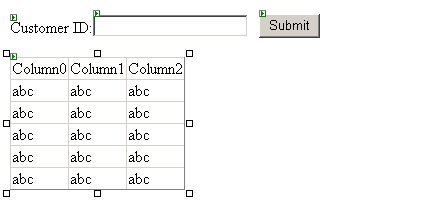

label. Drag and drop a DataGrid control from the Toolbox

onto the Web form directly below the Customer ID label. In the Properties Window,

change its (ID) property to

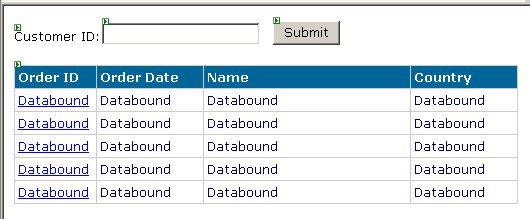

grdOrders. At this point, your Web form should look the same as the form shown

in Figure 10.

Figure 10. You drag and drop controls from the VS

.NET toolbox onto a Web form the same way as you do with a Windows Form.

If you’re not particularly fond of the default font for

controls on this form, you can easily change the fonts of all controls. First,

select all controls, go to the Properties Window, and expand the Font node. You can then

select different font attributes. In the sample code, I’ve selected a Font Name of “Verdana”

and a Font Size of

“Smaller”.

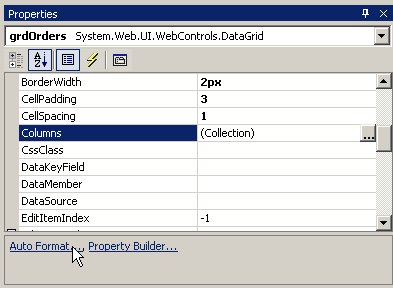

Next, you can improve the appearance of the DataGrid by

applying an auto-format style to it. With the DataGrid selected in design mode,

go to the Properties Window, and click the AutoFormat

hyperlink label (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Select the Auto Format hyperlink in

the Properties Window to automatically apply a visual style to a DataGrid.

In the Auto Format dialog,

select any scheme you want, but for this example, I chose “Professional 2”.

After selecting the scheme, click OK

to apply the scheme to the DataGrid.

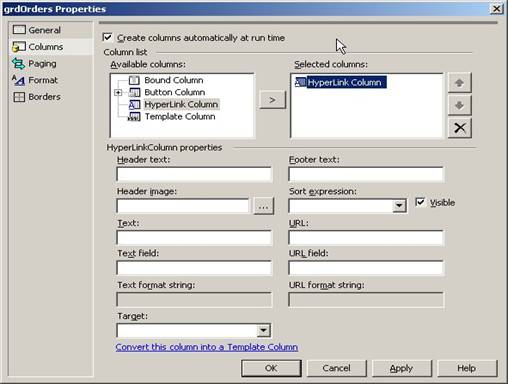

Now it’s time to specify columns for the DataGrid. Click on

the DataGrid in design mode and go to the Properties Window. Select the Columns property and

click the ellipses button (…) next to the Columns

property. This launches the grdOrders

Properties dialog allowing you to add one or more columns to the

DataGrid. You are going to add four columns to the grid that hold Order ID,

Order Date, Ship Name, and Ship Country.

First, uncheck the Create

columns automatically at run time box at the top of the dialog.

This prevents columns from being automatically generated from the data source

at rum time. You don’t need them dynamically generated because you are going to

manually specify all columns at design time.

Notice this dialog has a mover box that lets you add items

from the left side of the mover to the right side. In the left mover list box,

there are four different column types to choose from:

·

Bound column

·

Button column

·

Hyperlink column

·

Template column

The Bound Column

option creates a column bound to a data source. The Button

Column option allows you to add buttons to the DataGrid that the

user can click, usually to start off some process or to edit, update, or delete

items in the DataGrid. The Hyperlink

Column allows you to add a hyperlink label to a column that the

user can click, which usually redirects them to another form where they can

edit the selected item. A Template

Column allows you to create a column containing any combination

of HTML, text, and controls.

For the first column, add a hyperlink column containing the

Order ID. This allows users to click on the column to select an order to be

edited. It also launches an Order Edit page and passes the ID of the selected

Order to that page. To add this column, select Hyperlink

Column in the Available

columns list, and then click the mover button ( > ) to add the

column to the Selected

columns list. When you do this, it displays HyperLinkColumn properties

at the bottom of the dialog (Figure 12).

Figure 12. The Web Forms DataGrid Properties

dialog allows you to add a variety of columns to your DataGrid.

In the Header text

box and the Text field box,

enter “Order ID”. This sets the OrderID field as the data source for the

hyperlink text displayed in this column. In the URL

field box, enter “OrderID”, and in the URL

format string box enter “OrderEdit.aspx?orderID={0}”. The URL field specifies the

data source field containing the value to be passed to the target page—in this

case, the OrderID field. The first part of the URL

format string (OrderEdit.aspx) specifies the target Web page

requested when a user clicks on an Order ID hyperlink. The second part of the URL format string

(?orderID={0}) specifies a parameter named “orderID” is passed to the target

page. The “{0}” is a substitution parameter. ASP.NET substitutes the value of

the field specified in the URL

field text box (in this case OrderID) when it creates the link at

run time. For example, if the currently selected order ID is 10372, the link

created is:

OrderEdit.aspx?orderID=10372

The value of the orderID parameter is easily retrieved from

within the OrderEdit page you will soon create.

Now add a bound column to the DataGrid by selecting Bound Column in the Available

columns list and clicking the mover button. When you do this, a different set

of properties displays in the bottom half of the dialog. In the Header text box, enter

“Order Date” and in the Data field

box enter “OrderDate”.

Add another bound column to the DataGrid and set its Header text to “Name” and

its Data field to

“ShipName”. Next, add one more bound column to the DataGrid, settings its Header text to “Country”

and its Data field to

“ShipCountry”.

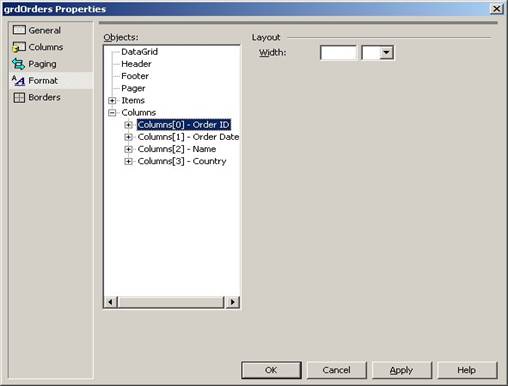

Now, set the width of each column in the DataGrid. In the

left pane of the grdOrders

Properties dialog, select Format.

When you do this, a TreeView named Objects

is displayed in the right side of the dialog. Select the Columns node and you will

see the four columns you just added to the DataGrid. Select the first column

(Columns[0]) and a Width

text box and associated combo box are displayed (Figure 13).

Figure 13. You can set the widths of DataGrid

columns in the Properties dialog.

In the Width

text box, enter 75 for the Order ID column. When you enter the width, a “px”

(an abbreviation for “pixels”) displays in the combo box—just accept the “px”

setting. Next, set the width of the Order Date column to 100, the Name column

to 200, and the Country column to 100. When you’re done, click the OK button to close the

dialog and apply the new column settings to your DataGrid. If you look at the

CustomerOrders form in design mode, it should look like Figure 14.

Figure 14. The DataGrid in design mode reflects

column settings you apply in the DataGrid’s Properties dialog.

Next, change the background color of the Web form to grey.

Click on the Web form in design mode, go to the Properties Window, and select

the bgColor property.

Click the ellipses button (…) next to the property to launch the Color Picker dialog. You

can pick any color you like, but for this example, I selected the Named Colors tab, and

selected the “Gainsboro” grey color in the far right center of the color

palette (Figure 15). Click the OK

button to select the color.

Figure 15. You can set the background color of a

Web form using the Color Picker

Now you need to set up data access for the form by reusing

business objects created for your Windows Forms application in the previous

chapter.

In Chapter 9, “Building .NET Windows Forms

Applications”, you created three different business objects—Orders, OrderItem,

and Shipper. You can use these same business objects in your Web Forms

application. There are a few ways to accomplish this, but the easiest method

right now is adding the source code files to your Web Forms application.

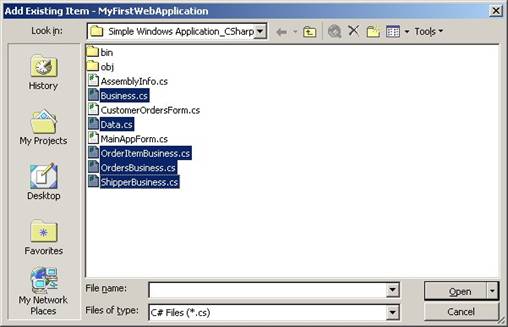

To add these source code files, right-click your Web Forms

project in the Solution Explorer and select Add

| Add Existing Item from the shortcut menu. In the Add Existing Item dialog,

navigate to the “Simple Windows Application” directory you created in the

previous chapter, and select the five business object source code files (Figure

16). These are Business.cs, Data.cs, OrderItemBusiness.cs,

OrderBusiness.cs, and ShipperBusiness.cs. If you created a Visual Basic .NET

Windows Forms application, these files will have a “vb” extension rather than a

“cs” extension. After selecting all five files, click the Open button.

Figure 16. You can add files belonging to one

.NET project to any other .NET project

After clicking the Open

button, these five files should be listed in the Solution Explorer.

Typically, with business objects that are going to be used from

multiple projects, you should create a separate Class Library project in Visual

Studio .NET and add your business object source code files to this project. You

can then compile a DLL containing just your business object classes. This DLL

can then be referenced from multiple projects (such as a Windows Form

application and a Web Forms application).

Now you need to add code to the Web form to retrieve data

from the business object that is displayed in the Orders DataGrid. To do this,

edit the CustomerOrders.aspx.cs (C#) or CustomerOrders.aspx.vb (VB .NET) code

file. At the top of the code file, add the following namespace reference.

In C#:

using HW.NetBook.Samples.Business;

And in Visual Basic .NET:

Imports HW.NetBook.Samples.Business

Go back to the CustomerOrders form in design mode and

double-click the Submit

button. This automatically adds an event handler to the code-behind file. Add

the following code to this event handler.

In C#:

private void btnSubmit_Click(object sender,

System.EventArgs e)

{

// Instantiate the Orders

business object

Orders OrderObj = new

Orders();

// Get all Orders for the

user-specified customer and bind

// the DataGrid to the

resulting DataSet

DataSet ds =

OrderObj.GetOrdersByCustomerID(this.txtCustomerID.Text);

this.grdOrders.DataSource

= ds;

this.grdOrders.DataBind();

}

In Visual Basic .NET:

Private Sub btnSubmit_Click(sender As Object, e As

System.EventArgs) _

Handles

btnSubmit.Click

' Instantiate the Orders

business object

Dim OrderObj As New

Orders()

' Get all Orders for the

user-specified customer and bind

' the DataGrid to the

resulting DataSet

Dim ds As DataSet =

OrderObj.GetOrdersByCustomerID(Me.txtCustomerID.Text)

Me.grdOrders.DataSource

= ds

Me.grdOrders.DataBind()

End Sub 'btnSubmit_Click

This code instantiates the Orders business object, calls its

GetOrdersByCustomerID method, and passes the value of the Customer ID text box.

It then binds the DataGrid to the resulting DataSet.

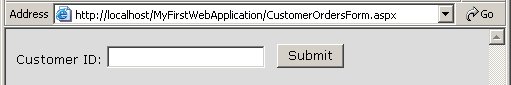

Now you’re ready to test the Customer Orders Web form

to see if what you’ve done so far is working properly. To do this, select Build | Build Solution from

the menu. If everything compiles correctly, run the Web Forms application by

pressing F5 or click the Run button (if it doesn’t compile correctly, fix the

errors and compile again). When Internet Explorer opens, you should see the Customer ID label and

text box as well as the Submit

button (Figure 17).

Figure 17. When you run the Web Forms

application, it displays the Customer ID label and text box as well as the

Submit button.

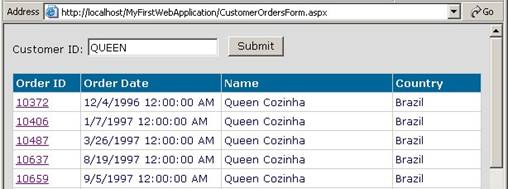

To test the application’s data access abilities, enter the

text “QUEEN” in the Customer ID

text box and click the Submit

button. After a few moments, you should see a list of orders displayed in the

Orders DataGrid (Figure 18).

Figure 18. When you enter a customer ID, the

customer’s orders are displayed in

the DataGrid.

the DataGrid.

At this point, if you try to click on any of the order ID

hyperlink labels, you would get an error, because you haven’t created the Order

Edit Web form. You’ll do this soon, but first take a closer look at what’s

happening behind the scenes.

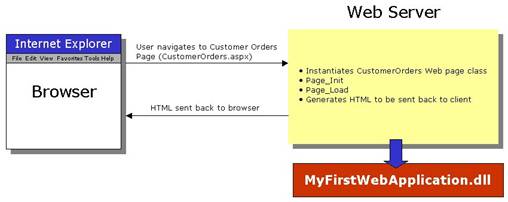

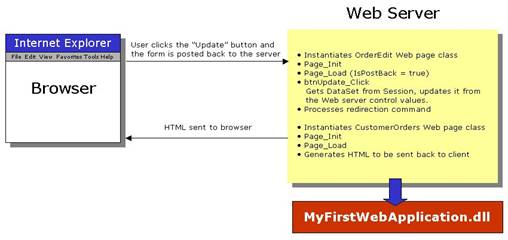

When you first run the Web Forms application the

following occurs (see also Figure 19):

1.

The browser sends a request to the Web server for the

CustomerOrders.aspx page.

2. The

Web server receives the request and instantiates the CustomerOrders Web

page class.

page class.

3. The

Web page’s Page_Init event fires.

4. The

Web page’s Page_Load event fires.

5. The

Web server processes the page and sends HTML output back to the browser.

6. The

browser renders the HTML for display to the user.

Figure 19. When a client browser requests an

ASP.NET Web page, the server instantiates the associated page class and

generates HTML, which is sent back to the browser to be rendered.

To see the HTML passed back to the browser, run the

application, and when the page is initially displayed in the browser, select View | Source from the

menu. You should see HTML that looks something like this:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0

Transitional//EN" >

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<title>WebForm1</title>

<meta content="Microsoft Visual Studio 7.0"

name="GENERATOR">

<meta

content="C#" name="CODE_LANGUAGE">

<meta

content="JavaScript" name="vs_defaultClientScript">

<meta

content="http://schemas.microsoft.com/intellisense/ie5"

name="vs_targetSchema">

</HEAD>

<body bgColor="gainsboro">

<form name="Form1" method="post"

action="CustomerOrders.aspx" id="Form1">

<input

type="hidden" name="__VIEWSTATE"

value="dDwxMTU0MzQ2MTEzO3Q8O2w8aTwxPjs+O2w8dDw7bDxpPDc+Oz47bDx0PEAwPDs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs+Ozs+Oz4+Oz4+Oz6oG5OBeOfpfCgjFYH5BiaCehjOwg=="

/>

<P>

<span id="lblCustomerID"

style="font-family:Verdana;font-size:Smaller;">Customer

ID:</span>

<input name="txtCustomerID" type="text"

id="txtCustomerID"

style="font-family:Verdana;font-size:Smaller;" />

<input type="submit" name="btnSubmit"

value="Submit" id="btnSubmit"

style="font-family:Verdana;font-size:Smaller;" /></P>

<P>

</P>

</form>

</body>

</HTML>

In addition to the normal HTML you would expect to see,

notice there is also a hidden “input” element located in the middle of the HTML

with the name “_VIEWSTATE” and a value string of seemingly incomprehensible

characters. This hidden field is the mechanism used by ASP.NET to transfer page

state information between the browser and the server. In the context of

a Web page, “state” refers to the values of a Web page’s variables and

controls. Since the Web is a stateless environment, you need some mechanism to

store and retrieve the state of a page as it gets passed back and forth between

the browser and the server.

To understand more fully how this works, take a look at the

sequence of events occurring when a user retrieves orders for a specified

customer using your Web application.

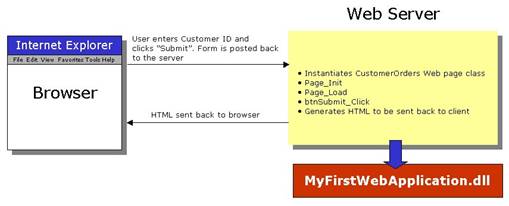

When the user enters a customer ID and clicks the Submit button, the

following occurs (see also Figure 20):

1.

Clicking the Submit

button raises the Click event on the browser.

2. The

CustomerOrders page posts back to the Web server, including the value entered

by the user in the Customer ID text box.

3. In

response, the Web server instantiates the CustomerOrders Web page class.

4. The

Web page’s Page_Init event fires.

5. The

Web page’s Page_Load event fires.

6. The

event handler for the Submit button’s Click event (btnSubmit_Click) is executed

to respond to the Click event raised on the browser.

7. The

btnSubmit_Click event handler code instantiates the Orders business object,

retrieves the Customer ID value from the text box, and passes it to the

object’s GetOrdersByCustomerID method.

8. The

Orders DataGrid is bound to the DataSet returned from the Orders object.

9. The

Web server processes the page again and sends HTML back to the browser.

Figure 20. During a round-trip, a Web form is

posted to the server, processed, and sent back to the browser again.

If you view the source code in your browser again, this time

you’ll see HTML for the DataGrid. In addition, you’ll notice the state stored

in the hidden field is considerably larger than before. This is because it now

contains state information for the DataGrid that was passed back from the Web

server.

Now we need to create an Order Edit Web form that lets

users edit a selected order. In the Solution Explorer, right-click on the

project node and select Add | Add Web

Form from the shortcut menu to launch the Add New Item dialog with

the Web Form template

pre-selected. In the Name

text box, change the name of the Web form to OrderEdit.aspx, and then click the

Open button. This opens

the new OrderEdit form in design mode. For this form, leave the pageLayout property set

to “GridLayout”. This gives you a similar feel as creating Windows forms—you

can position controls anywhere on the design surface.

Next, go to the Properties Window and select the bgColor property. Click

the ellipses button (…) next to the property to launch the Color Picker dialog.

Again, as you did for the CustomerOrders form, click the Named Colors tab and

select the “Gainsboro” grey color on the far right center of the palette.

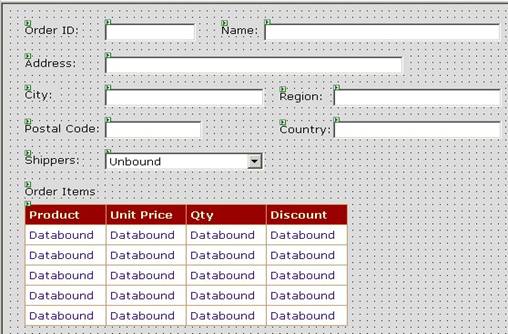

Now you’re ready to drop some controls on the Web form. First

select the Web form in design mode. For easier placement of controls, select Format | Snap to Grid

from the main menu. Next, drag and drop the controls listed in Table 4

on the form, setting their ID

and Width properties

as specified in the table. Note that the Size setting in Table 4 is only a

suggestion—you can set the size to any value you wish. For an idea of where to

locate the controls, see Figure 21.

Table 4. Class, ID, text, and size of controls on

the Order Edit Web form

Class

|

Control ID

|

Text

|

Size

|

Label

|

lblOrderID

|

Order ID:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtOrderID

|

100

|

|

Label

|

lblName

|

Name:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtName

|

260

|

|

Label

|

lblAddress

|

Address:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtAddress

|

328

|

|

Label

|

lblCity

|

City:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtCity

|

175

|

|

Label

|

lblRegion

|

Region:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtRegion

|

185

|

|

Label

|

lblPostalCode

|

Postal Code:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtPostalCode

|

107

|

|

Label

|

lblCountry

|

Country:

|

-

|

TextBox

|

txtCountry

|

185

|

|

Label

|

lblShippers

|

Shippers:

|

-

|

DropDownList

|

cboShippers

|

175

|

|

Label

|

lblOrderItems

|

Order Items

|

-

|

DataGrid

|

grdOrderItems

|

355

|

Again, if you want to change the font of all controls on this

form, drag a “lasso” around the controls to select them all, go to the

Properties Window, and change the Font

properties to whatever you like. In the sample code, I’ve changed the Font Name to “Verdana”

and the Font Size to

“Smaller”.

Now select a color scheme for the Order Items DataGrid.

Select the DataGrid in design mode and click the AutoFormat hyperlink label at the

bottom right of the Properties Windows (Figure 11). In the Auto Format dialog choose

a scheme from the list and click OK

to close the dialog (in the sample code, I’ve selected the “Colorful 1”

scheme).

Next, add columns to the Order Items DataGrid. Select the

DataGrid in design mode, go to the Properties Window, and select the Columns property. Click

on the ellipses (…) button next to the Columns

property to launch the DataGrid

Properties dialog. First, uncheck the Create

columns automatically at run time checkbox, and then add four

bound columns to the DataGrid as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Properties for columns in the DataGrid on

the Order Edit Web form

Column Type

|

Header Text

|

Data Field

|

Bound Column

|

Product

|

ProductID

|

Bound Column

|

Unit Price

|

UnitPrice

|

Bound Column

|

Qty

|

Quantity

|

Bound Column

|

Discount

|

Discount

|

Figure

21. When you set a Web form’s pageLayout property to GridLayout, you can

place controls on the form wherever you like—similar to a Windows form.

Figure

21. When you set a Web form’s pageLayout property to GridLayout, you can

place controls on the form wherever you like—similar to a Windows form.

Now it’s time create data access and data binding code for

the Shippers DropDownList and the Order Items DataGrid controls so they can

display their corresponding data at run time. Double-click the OrderEdit form

design surface, which places you in the Page_Load event handler method. Before

adding code to this method, go to the top of the code file and add the

following namespace reference.

In C#:

using HW.NetBook.Samples.Business;

And in Visual Basic .NET

Imports HW.NetBook.Samples.Business

Now go back down to the bottom of the code file and add the

following code to the Page_Load Event.

In C#:

private void Page_Load(object sender, System.EventArgs

e)

{

if (! IsPostBack)

{

// Get the Order ID

passed to this page

int OrderID =

int.Parse(Request.QueryString["orderID"]);

// Get the specified

order and data bind the order controls

Orders OrderObj = new

Orders();

DataSet dsOrder =

OrderObj.GetOrderByOrderID(OrderID);

DataRow drOrder =

dsOrder.Tables["Orders"].Rows[0];

// Persist the

DataSet to the Session state

Session["OrderDataSet"]

= dsOrder;

this.txtOrderID.Text

= drOrder["OrderID"].ToString();

this.txtName.Text =

drOrder["ShipName"].ToString();

this.txtAddress.Text

= drOrder["ShipAddress"].ToString();

this.txtCity.Text =

drOrder["ShipCity"].ToString();

this.txtRegion.Text =

drOrder["ShipRegion"].ToString();

this.txtPostalCode.Text

= drOrder["ShipPostalCode"].ToString();

this.txtCountry.Text

= drOrder["ShipCountry"].ToString();

// Get a list of all

shippers

Shipper ShipperObj =

new Shipper();

DataSet dsShippers =

ShipperObj.GetShippers();

// Get the index of

the row that should be preselected

int Index = 0;

foreach (DataRow dr

in dsShippers.Tables[ShipperObj.TableName].Rows)

{

if

((int)dr["ShipperID"] == (int)drOrder["ShipVia"])

{

break;

}

Index++;

}

// Data bind the

combo box

this.cboShippers.DataTextField

= "CompanyName";

this.cboShippers.DataValueField

= "ShipperID";

this.cboShippers.DataSource

= dsShippers;

this.cboShippers.SelectedIndex

= Index;

this.cboShippers.DataBind();

// Get all order

items for the specified order id

OrderItem

OrderItemObj = new OrderItem();

DataSet dsOrderItems

= OrderItemObj.GetOrderItems(OrderID);

this.grdOrderItems.DataSource

= dsOrderItems;

this.grdOrderItems.DataBind();

}

}

And in Visual Basic .NET

Private Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As System.Object, _

ByVal e As

System.EventArgs) Handles MyBase.Load

If Not IsPostBack Then

' Get the Order ID

passed to this page

Dim OrderID As

Integer = Integer.Parse(Request.QueryString("orderID"))

' Get the specified

order and data bind the order controls

Dim OrderObj As New

Orders()

Dim dsOrder As

DataSet = OrderObj.GetOrderByOrderID(OrderID)

Dim drOrder As

DataRow = dsOrder.Tables("Orders").Rows(0)

' Persist the

DataSet to the Session state

Session("OrderDataSet") = dsOrder

Me.txtOrderID.Text

= drOrder("OrderID").ToString()

Me.txtName.Text =

drOrder("ShipName").ToString()

Me.txtAddress.Text

= drOrder("ShipAddress").ToString()

Me.txtCity.Text =

drOrder("ShipCity").ToString()

Me.txtRegion.Text =

drOrder("ShipRegion").ToString()

Me.txtPostalCode.Text = drOrder("ShipPostalCode").ToString()

Me.txtCountry.Text

= drOrder("ShipCountry").ToString()

' Get a list of all

shippers

Dim ShipperObj As

New Shipper()

Dim dsShippers As

DataSet = ShipperObj.GetShippers()

' Get the index of

the row that should be preselected

Dim Index As

Integer = 0

Dim dr As DataRow

For Each dr In

dsShippers.Tables(ShipperObj.TableName).Rows

If

CInt(dr("ShipperID")) = CInt(drOrder("ShipVia")) Then

Exit For

End If

Index += 1

Next dr

' Data bind the

combo box

Me.cboShippers.DataTextField = "CompanyName"

Me.cboShippers.DataValueField = "ShipperID"

Me.cboShippers.DataSource = dsShippers

Me.cboShippers.SelectedIndex = Index

Me.cboShippers.DataBind()

' Get all order

items for the specified order id

Dim OrderItemObj As

New OrderItem()

Dim dsOrderItems As

DataSet = OrderItemObj.GetOrderItems(OrderID)

Me.grdOrderItems.DataSource = dsOrderItems

Me.grdOrderItems.DataBind()

End If

End Sub

First this code checks the form’s IsPostBack property to

determine if the page is being loaded for the first time or in response to a

post back from the Web browser. If it’s being loaded in response to a post back,

all of the code in this method is bypassed. This is necessary because running

this code on a post back would overwrite any changes the user makes to the

order.

If IsPostBack is false, the code in this method retrieves the

value of the orderID parameter passed to it from the CustomerOrders page. It

does this by calling the ASP.NET Request object’s QueryString method, passing

the name of the parameter. The QueryString method returns a string value that

is converted into an integer.

Next, the code instantiates the Orders object and calls its

GetOrderByOrderID method, passing the order ID received from the Customer

Orders page. Notice after retrieving the DataSet from the Orders object, it

persists the DataSet to the Session object. This is done because later in this

particular example you are going to update the selected order stored in the

DataSet. Storing the DataSet in the Session state allows you to retrieve the

DataSet from the Session object when the update is performed. If you didn’t

persist the DataSet, you would lose all of your changes when the form is posted

back to the Web site.

After persisting the Orders DataSet, controls are bound to

the DataSet. Next, DataSets

are retrieved from the Shippers and OrderItems business objects and the controls are bound

to data.

are retrieved from the Shippers and OrderItems business objects and the controls are bound

to data.

Here’s a special note about binding to a DropDownList

control. If you want to pre-select an item in the DropDownList control, the

only way you can do this is by setting its SelectedIndex property. However,

when you bind to a DataSet, there’s no straightforward way to retrieve the

index of the DataRow you want selected. That’s why there’s a “for each” loop in

this method—it loops through the DataRows to find the index of the Shipper

DataRow whose Shipper ID field contains the same value as the Order’s ShipVia

field. It would be much better if Microsoft came up with an easier

way to do this—perhaps by means of a SelectedValue property.

Here’s another

important point—typically, in a Web forms application, if you need to retrieve

data from the back end for read-only purposes, you can use a DataReader and

Data Command object rather than a DataSet, since a DataReader provides faster

(though read-only) access to data. This means any place in the application

where I require read-only data (as in the case of Shippers) then I would use a

DataReader rather than a DataSet. For more information on using a DataReader,

see Chapter 7, “Data Access with ADO.NET”.

Now it’s time to test your work on the Order Edit form

so far. Compile and run the Web application by pressing the Start button or pressing

F5. The Customer Orders Web form appears first. Enter the word “QUICK” in the

Customer ID text box and click Submit. This fills the Orders DataGrid with all

orders for the specified customer.

Click on any hyperlink label in the Order ID column to

display the Order Edit form (Figure

22).

Figure 22. The Order Edit Web form knows the

order to display based on the orderID parameter passed to it from the Customer

Orders page.

If you take a close look at Internet Explorer’s Address box at the top of

Figure 22, you’ll see a string “?orderID=10285” at the end of the URL. This is

the order ID selected in the Customer Orders form. This parameter is passed to

the Order Edit form when you click on the hyperlink label in the first column

of the Order Items DataGrid. This value is also used in the Order Edit page to

retrieve data from the Orders and OrderItem business objects.

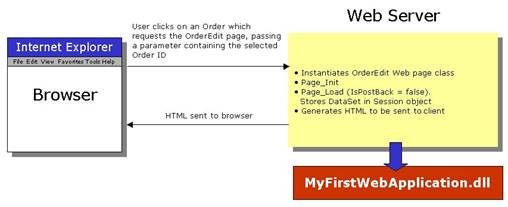

When the user clicks on an Order in the CustomerOrders

form, the following occurs (see Figure 23 also):

1.

A request is sent to the Web Server for the OrderEdit

Web page. In this request, an orderID parameter is passed containing the

selected order ID.

2. The

Web server receives the request and instantiates the OrderEdit Web page class.

3. The

Web page’s Page_Init event fires.

4. The

Web page’s Page_Load event fires. Within this event, a check is performed to

determine if the page is being loaded for the first time or in response to a

post back. In this case, it’s the first time the page is loaded, so the Orders

business object is instantiated, a DataSet containing the order returns from

the Orders object, and the Web server controls are bound to the DataSet.

5. All

order items are retrieved from the Order Items business object and the Order

Items DataGrid is bound to this DataSet.

6. The